An investor holds a concentrated stock position worth $3M with a $1M cost basis. They live in California, and if they sell today, their long-term capital gains tax rate would be approximately 36.1% (20% federal, 3.8% NIIT, and 12.3% California state). Selling the position would result in roughly $700K in taxes, immediately reducing the portfolio.

721 Exchange Funds

The investor knows that by delaying paying capital gains, they can potentially increase their post-tax returns.

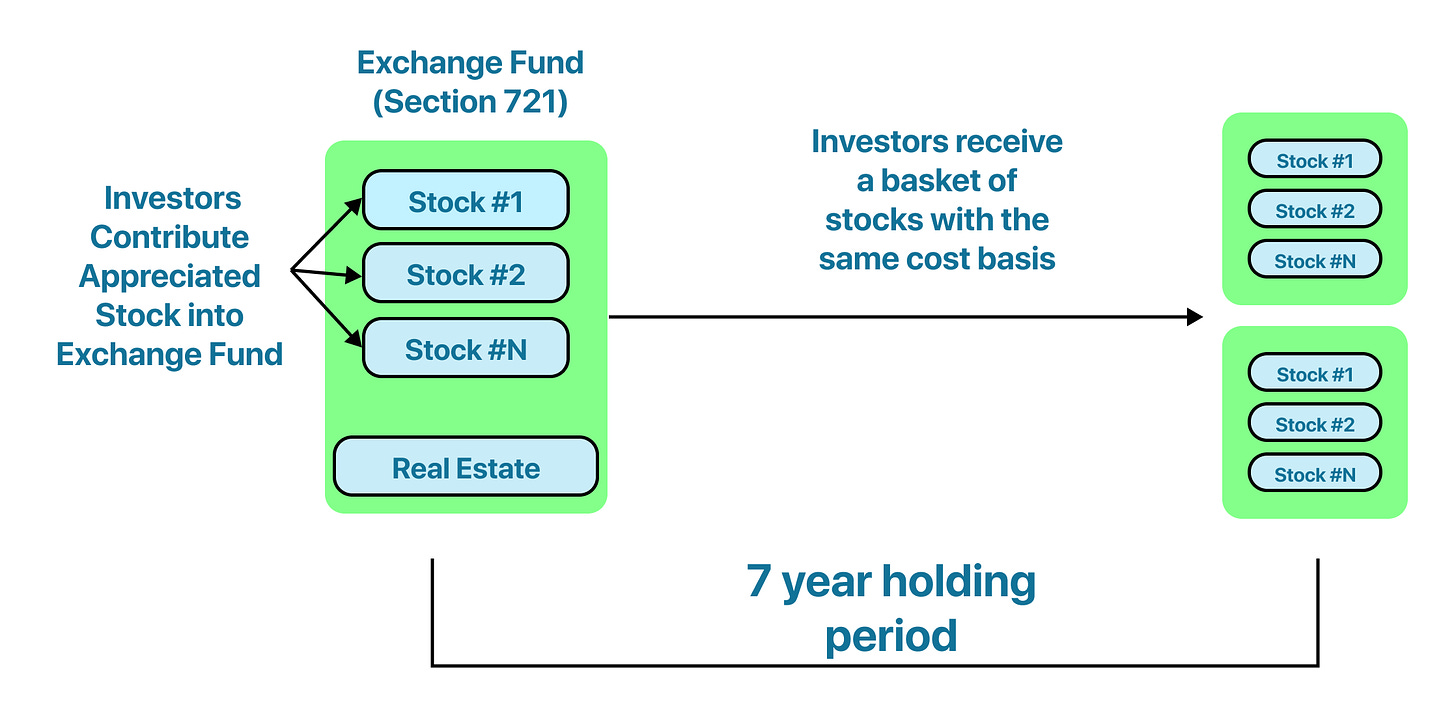

Instead of selling, the investor joins an Exchange Fund to diversify in a tax-efficient way. The investor contributes their appreciated stock to a partnership and, in return, receives an interest in that partnership. No gain is recognized at contribution because Section 721 of the Internal Revenue Code says:

721(a): No gain or loss shall be recognized to a partnership or to any of its partners in the case of a contribution of property to the partnership in exchange for an interest in the partnership.

That’s why these vehicles are often referred to as “721 Exchange Funds”—they are partnerships relying on IRC §721.

The IRS imposes several important constraints:

No single contributor (or related group) may control the partnership (50% or more ownership) after contribution.

At least 20% of the fund’s assets must be invested in “qualifying” illiquid assets, typically real estate.

Investors generally must remain in the partnership for about 7 years to receive a diversified basket of securities without recognizing capital gains.

Because an exchange fund is a pass-through entity, all gains and losses realized by the partnership flow through to investors. If contributed stocks pay dividends or if the fund manager sells any securities, those gains are passed directly to partners.

The Exchange Fund manager now has a choice. They either can:

Sell ~20% of contributed stock to purchase real estate, or

Borrow money, using contributed stock as collateral, to acquire real estate investments.

The first approach reduces tax efficiency by realizing gains investors hoped to defer. The second increases investment risk by introducing leverage.

During the dot-com crash, the NASDAQ fell nearly 80% between March 2000 and September 2002. An important question, therefore, is: What happens if the collateral used to finance the real estate portion of the fund drops by 80%?

If the fund faces a margin call and cannot post additional collateral, it may be forced to liquidate positions, realizing capital gains at precisely the worst possible time: during a market downturn.

Bottom line: If you’re considering an exchange fund, you should ask how the manager satisfies the IRS 20% requirement, as this directly affects your risk exposure.

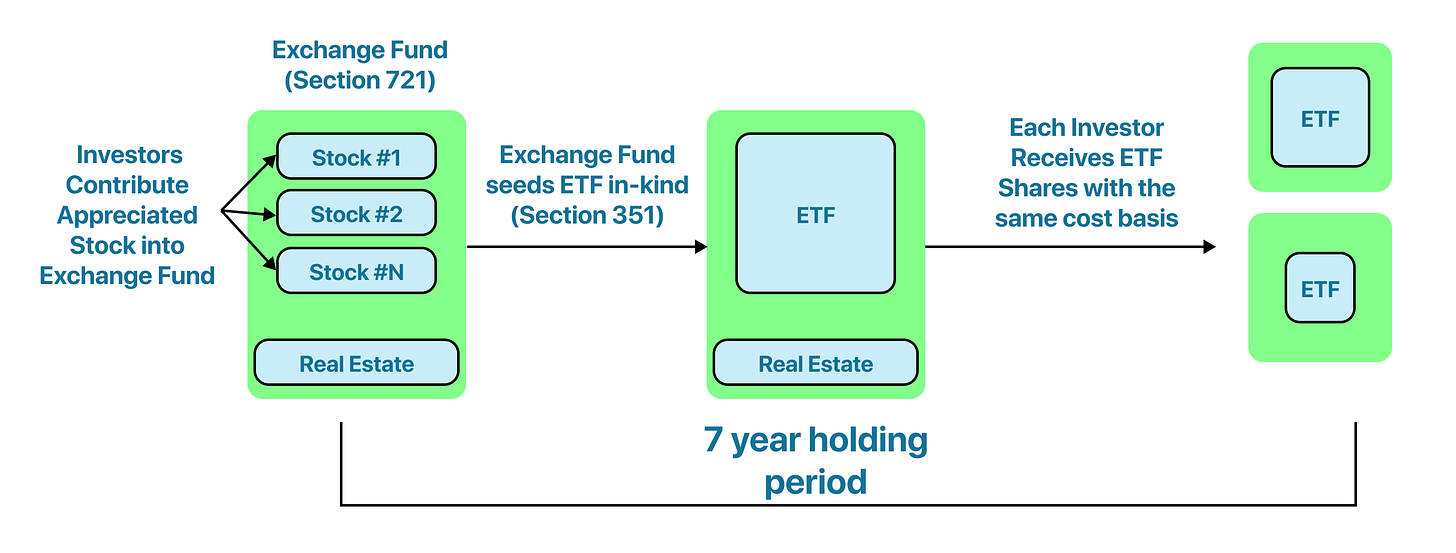

351 ETF Exchange Within Exchange Funds

Rebalancing an exchange fund portfolio is highly constrained. Most contributed stocks have low cost basis, and selling them would trigger capital gains that pass through to investors. To maintain index-like exposure and limit tracking error, many exchange funds use a secondary strategy known as a 351 ETF Exchange.

Under Section 351 of the Internal Revenue Code, investors can contribute appreciated stock to help “seed” a new ETF. In exchange, they receive shares of the ETF. Because this is an “in-kind” contribution to a newly formed entity, it does not trigger an immediate capital gains tax. Your original cost basis simply transfers to the new ETF shares.

351(a): (a) General rule

No gain or loss shall be recognized if property is transferred to a corporation by one or more persons solely in exchange for stock in such corporation and immediately after the exchange such person or persons are in control (as defined in section 368(c)) of the corporation.

Once the ETF is launched, the appreciated stocks can be sold inside the ETF without triggering a taxable event for the exchange fund partnership. For this reason, these structures are sometimes referred to as “351 Exchange Funds.”

At the end of the typical 7-year period, investors in a 721 exchange fund may receive ETF shares rather than a basket of individual securities.

ETF management fees often range from 0.2%–0.4%. It’s important to ask whether these fees are included in the exchange fund’s stated fee or layered on top.

Exchange funds themselves are expensive, with annual fees typically between 0.4% and 1%. For a $3M position over 7 years (assuming 10% annual growth), this can translate into $160K–$262K in fees. Adding an additional 0.4% ETF layer could cost another ~$125K over the same period.

Standalone 351 ETF Exchange

A 351 ETF Exchange can also be done outside of a 721 exchange fund. This approach can significantly reduce fees and avoids the additional risk of implicit real estate exposure and leverage.

However, standalone 351 conversions must meet strict IRS diversification tests:

25% rule: No single holding may exceed 25% of the contributed assets.

50% rule: The top five holdings may not exceed 50% of total assets.

Because of these rules, an investor cannot simply swap 100% of a single concentrated stock into a new ETF. A mix of assets must be contributed to satisfy diversification requirements.

This isn’t an instant trade. Managers like Alpha Architect or Cambria schedule these launches in advance. During the onboarding period, your stock remains exposed to market volatility.

If you attempt to meet the diversification test by contributing an ETF (such as VTI) alongside your concentrated stock, the IRS applies a “look-through” rule. If VTI contains 5% of your concentrated stock, that exposure counts toward your 25% limit.

You should also ensure that all conversions are reported correctly when you file your tax returns. Reporting errors and mistakes do happen. It might be a very good idea to work with your CPA to verify correctness of reported transactions.

Learn More

We recently hosted a personal finance learning session where Marcel Miu, CFP, joined us to discuss the nuances of 351 exchanges and exchange funds.

You can watch the recording here: