We had a learning session last week focused on one of the most important but often misunderstood parts of financial planning: building realistic projections.

A solid financial plan typically follows this order:

Understand your current situation

Build realistic financial projections (income, expenses, taxes)

Define your financial goals

Construct portfolios aligned with those goals

Do tax planning on top of everything else

In our November 7th session, we focused on step 2, financial projections, and discussed the most common modeling mistakes we see people make. The conversation covered how small errors in assumptions about Social Security, healthcare, living expenses, and taxes can compound over time and distort a plan’s accuracy.

Here’s a condensed summary of that discussion, along with practical ideas for fixing each mistake.

1. Social Security: Ignored, Mis-Modeled, or Taxed Wrong

Mistake A: Ignoring Social Security entirely

High-income families often leave Social Security Benefits out of their projections. We understand the concern: “I don’t want to rely on it,” or “What if the system changes?” But for most people who’ve worked long enough, Social Security is real money: often $20K–$40K per year (in today’s dollars) for decades. Completely ignoring it usually makes the plan more confusing, not safer.

Instead, include Social Security in your projections—and if you’re concerned about potential cuts or means-testing, apply a discount (for example, model 50–70% of the estimated benefit) rather than dropping it to zero.

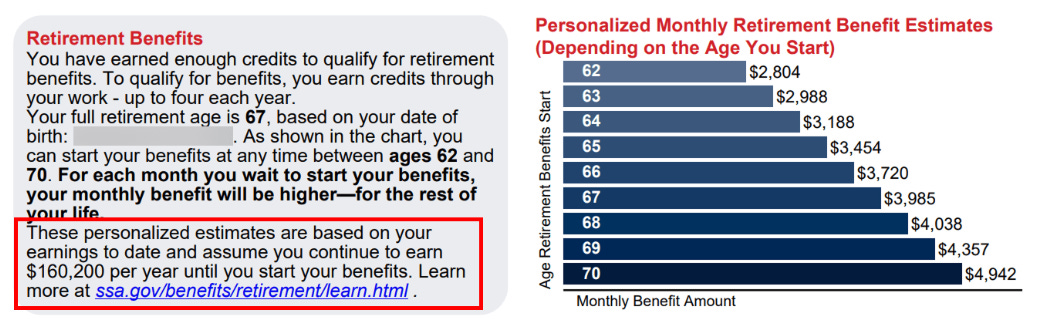

Mistake B: Using the SSA PDF at face value when retiring early

Many people pull their estimate from the Social Security website, see numbers for age 62, 67, 70, and plug those straight into their model. Those numbers usually assume you keep earning your current income until the claiming age. If you plan to stop working at 50, that estimate can be significantly inflated.

Instead, go to the SSA website and use the tool that lets you edit future earnings—set your income to what you actually expect: keep it similar if you plan to continue full-time, reduce it if you plan to work part-time, or set it to zero if you plan to stop working early—and then use those updated estimates in your projection.

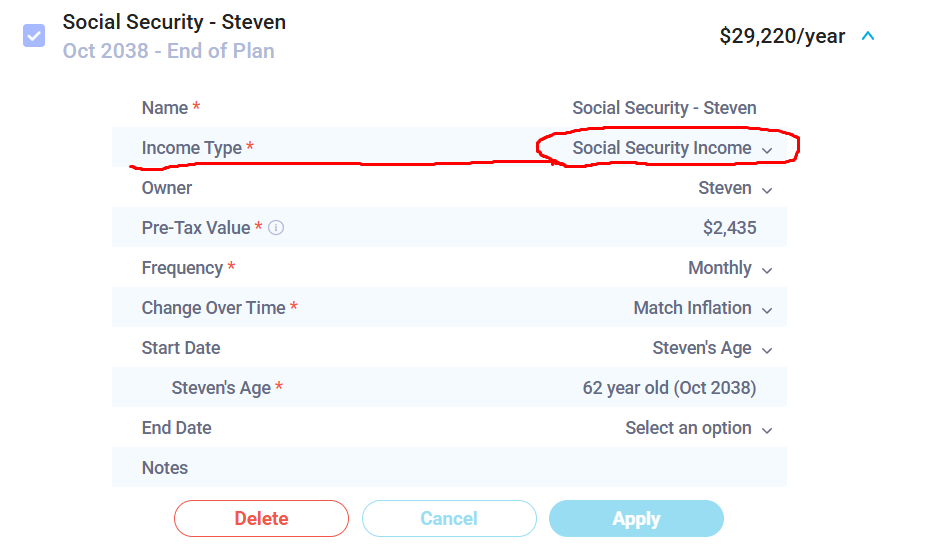

Mistake C: Treating Social Security as W-2 income in the model

Social Security is taxed differently from salary—only 0–85% of your benefit is taxable depending on your other income, so it’s not just another W-2 paycheck. If you label it as W-2 income in your planning tool, your tax calculations will likely be inaccurate, often too high.

Instead, use the specific “Social Security” income type (if available) and let the software apply the correct rules based on your total income each year.

2. Medical Expenses: Underestimated, Oversimplified, or Ignored

We rarely see people enter medical expenses manually. For early retirees especially, this is dangerous. Think of medical costs in three phases:

Pre-65: ACA / private coverage / COBRA

65+: Medicare + supplemental

Late life: Long-term care & support

Mistake A: Hand-waving medical costs

If you retire before 65, health insurance doesn’t disappear—it often becomes an important expense. Under the ACA, both premiums and subsidies depend heavily on your income, especially your taxable income. Common mistakes include underestimating the income used in ACA calculations (for example, Social Security is treated differently than it is for federal taxes, and tax-exempt muni bond interest still counts), forgetting that Roth conversions can increase ACA premiums, and not planning for potential changes to today’s subsidy rules.

Instead, model your pre-65 coverage explicitly: whether that’s ACA coverage with estimated premiums and maximum out-of-pocket costs, COBRA for up to 18 months (or 29 months if disabled in some cases), or private insurance.

For ACA plans, you can use your projected income to estimate premiums. A conservative approach works best: for each pre-65 year, plan to cover both the premium and the maximum out-of-pocket amount so you’re prepared for expensive years.

Mistake B: Ignoring the “gap” at very low income

If your income is too low, you could fall into a coverage gap in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid—people who aim for near-zero taxable income for tax purposes sometimes lose ACA subsidies by accident. Instead, make sure your projected income stays above your state’s ACA minimum thresholds, and if you’re intentionally keeping income low to qualify for subsidies, confirm you’re not slipping into the coverage gap.

Mistake C: Forgetting long-term care and “non-covered” health costs

Long-term care is costly—and most people need it only near the end of life, typically for 2–4 years. Yet we often see two extremes: no long-term care modeled at all, or overly conservative projections assuming 20 years of nursing home expenses. Both approaches can be misleading. People also tend to overlook expenses like dental, vision, acupuncture, chiropractic care, and other services that aren’t fully covered by Medicare or insurance.

Instead, model 2–4 years of long-term care near the end of life using realistic local cost estimates. Then decide whether to self-insure—by setting aside a dedicated bucket in your plan—or to purchase long-term care insurance. Self-insuring offers more flexibility and can be more cost-efficient for higher-net-worth families, while insurance may be better for those who struggle to save consistently. Finally, include a modest recurring budget for dental, vision, and other out-of-pocket health services.

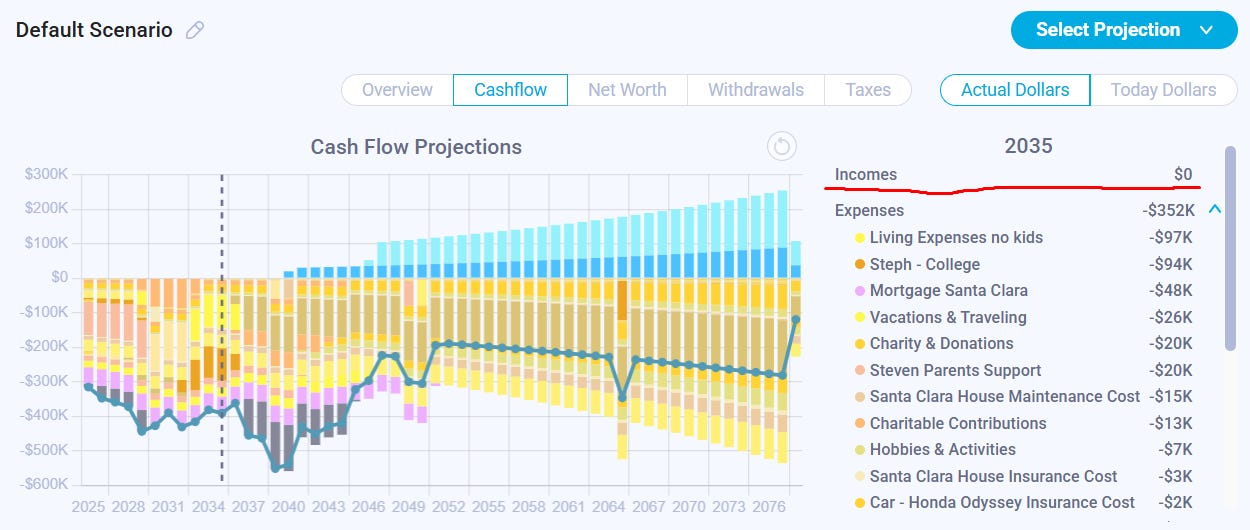

3. Living Expenses: One Giant Number for 40 Years

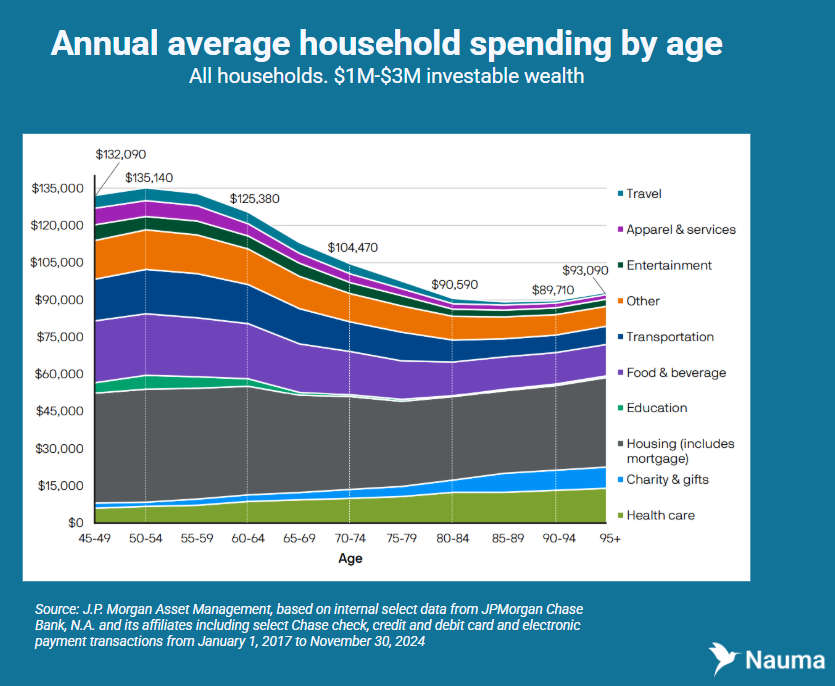

A common mistake is treating all living expenses as one flat number forever—like saying, “I spend $10,000 a month, so I’ll just project that with inflation for 40 years.” That approach ignores that different expenses follow different timelines: childcare and tuition eventually end, mortgages get paid off, early-retirement travel often spikes in the first 5–10 years then slows, and overall spending tends to decline later in life even as medical costs rise.

Instead, break your spending into a few broad categories with their own timelines—for example: baseline living expenses (food, utilities, transportation), child-related costs (daycare, private school) with end dates, big temporary “fun” goals (early-retirement travel, sabbaticals), support for aging parents, and gifts or charitable giving. You don’t need extreme detail—just separate expenses that clearly start or stop.

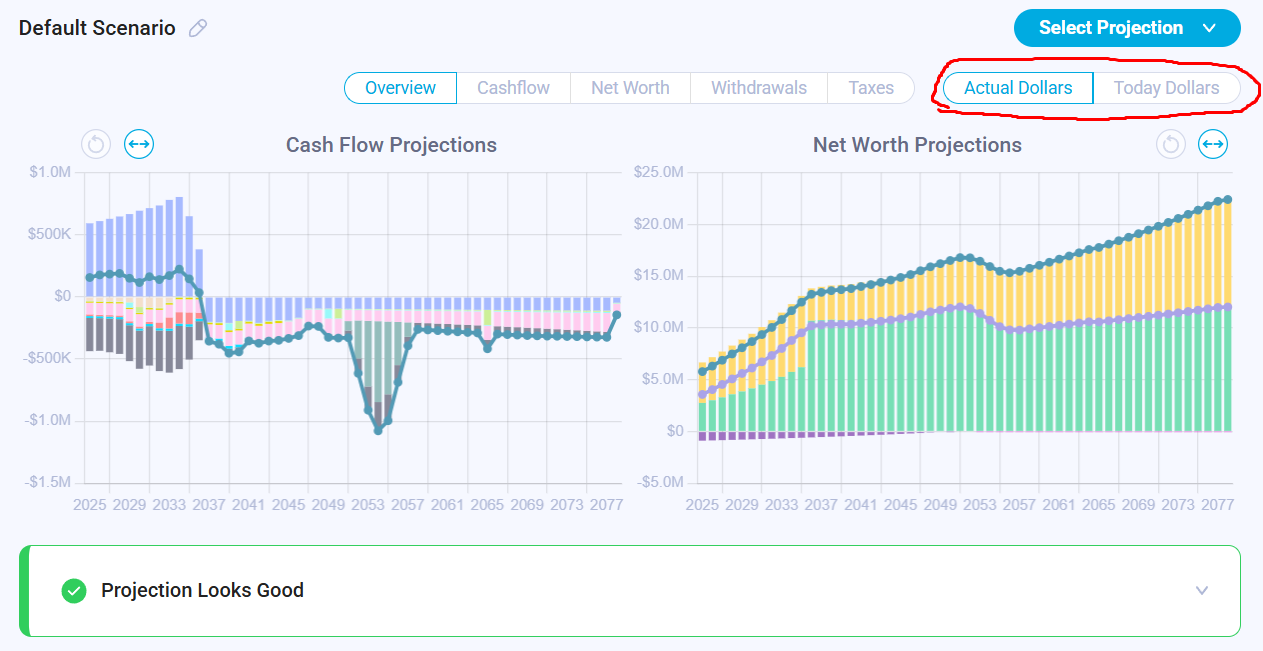

It’s also essential to view your projections in both today’s dollars and future (inflated) dollars: today’s dollars show the lifestyle your plan supports, while nominal dollars reveal what your actual future spending and balances will look like with inflation. Both perspectives matter.

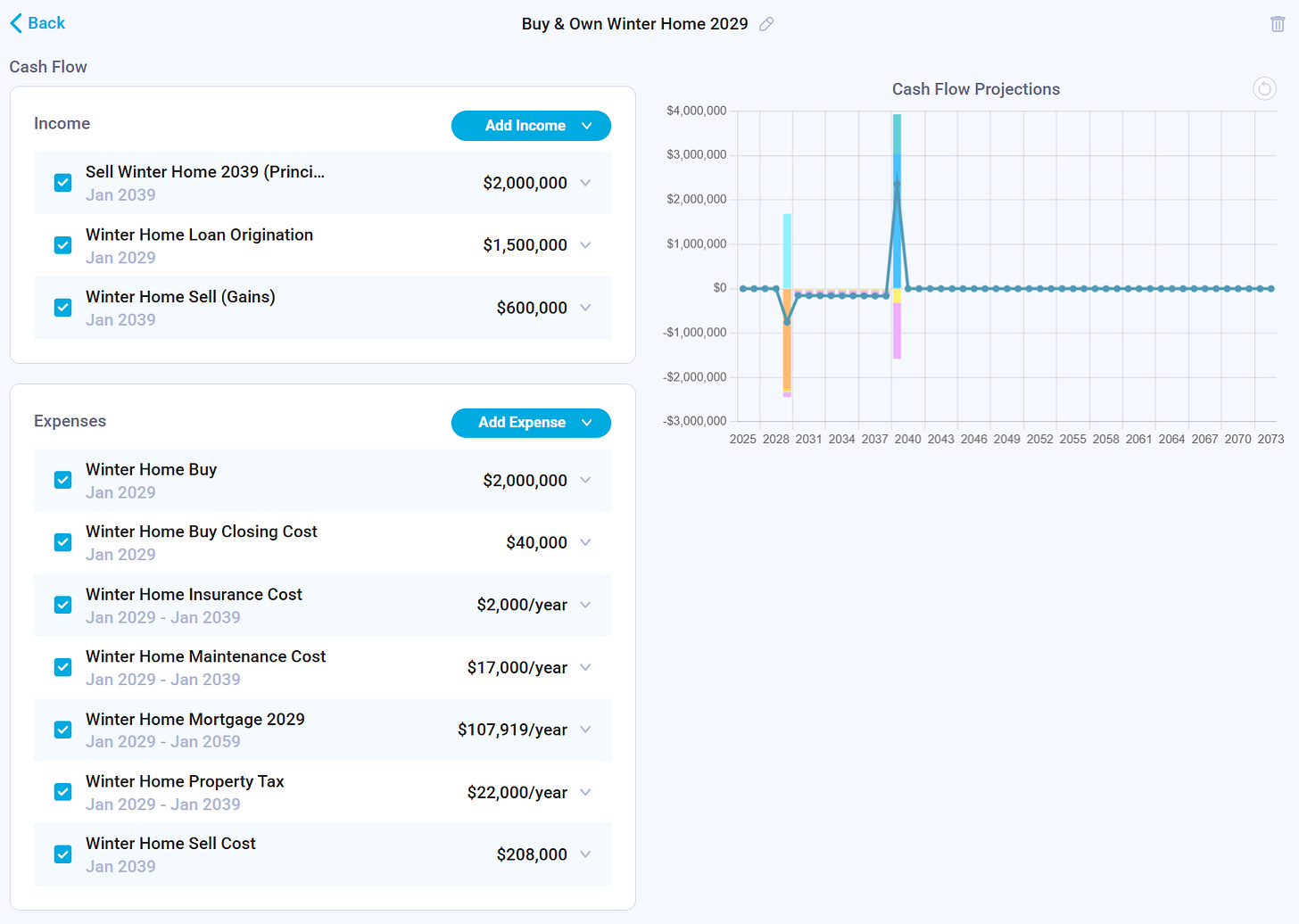

4. Homeownership: Underestimating the True Cost

When people talk about housing costs, they almost always focus on the mortgage—but the mortgage is time-limited (15–30 years) and often not the biggest long-term expense. The costs that tend to strain retirement plans are property taxes, HOA dues, insurance, and especially maintenance and major repairs.

Maintenance can seem minor most years—until you need to replace the roof, fix the foundation, repipe the house, or repaint the exterior. Those are five-figure expenses, and if you haven’t planned for them, you may end up pulling from investment accounts at bad times and triggering unnecessary taxes. A good rule of thumb is to plan for 1–1.5% of your home’s value per year in maintenance costs over the long run—some years will be light, others expensive, but it averages out reasonably over decades.

And don’t forget selling or moving. If you expect to downsize after the kids move out or relocate from a high-cost state, model those transitions explicitly—include realtor and transaction costs, potential capital gains taxes on appreciated property, and the new property taxes, insurance, and maintenance for your next home. These choices can cause visible “spikes” in your tax and cash flow projections, and seeing them charted helps you plan when and how to make the move strategically.

5. Unrealistic Growth, Inflation, and Tax Assumptions

The last category of mistakes is conceptual but hugely important.

Mistake A: Over-optimistic growth and inflation assumptions

We often see projections with unrealistic assumptions—income growing 10% a year for 20 years, medical or long-term care costs inflated at 10–12% for 30 years, or portfolios expected to earn 15–20% annually just because recent markets have been strong. But compounding works both ways—aggressive assumptions can make a fragile plan look bulletproof on paper.

Instead, use conservative, historically grounded assumptions for portfolio returns, inflation, and medical cost growth. Be especially careful with high growth rates over long time horizons (20–30 years)—they can make your numbers explode and give a false sense of security.

Mistake B: Treating taxes as a fixed percentage forever

Tax planning isn’t as simple as saying, “I’m in the 32% bracket today, so I’ll always be in the 32% bracket.”

Over a typical lifetime, your tax picture changes:

During peak earning years, taxes are high.

After you stop working but before RMDs and Social Security begin, taxes often drop.

Later, when RMDs and Social Security kick in, taxes can rise again.

Major events—like selling a business, exercising stock options, or buying and selling property—can create one-time tax spikes.

If your projection assumes a flat tax rate, you’ll miss major planning opportunities (like Roth conversions or timing large sales) and may underestimate future tax drag.

Instead, model different income types separately—salary, RSUs, Social Security, Roth conversions, RMDs, and so on—and let the software apply tax rules year by year. Look specifically for years with unusually low income (ideal for Roth conversions) and for years with large income spikes (from home or business sales, or option exercises) that could benefit from spreading income over multiple years when possible.

Bringing It All Together

A good financial projection isn’t about predicting the future perfectly—it’s about being honest about what you know today, staying conservative where uncertainty is high, and keeping your assumptions internally consistent.

If you thoughtfully include Social Security (perhaps with a discount), model pre-65 healthcare and long-term care realistically, separate temporary from recurring living expenses, account for the full cost of homeownership, and use reasonable assumptions for growth, inflation, and taxes—you’re already well ahead of most “back-of-the-envelope” plans.

From there, it finally makes sense to move on to discussions about asset allocation, withdrawal strategies, Roth conversions, and gifting or legacy planning.

You can watch the recording of this Learning Session here: