Raising kids is incredibly rewarding, but for people living in the San Francisco Bay Area it’s also financially intense. It takes up to $1M dollars to raise a kid and requires significant time commitment which often impacts the family’s other financial goals.

It’s a major financial decision and it deserves careful planning. Setting up a college fund remains a non-trivial task for many families as they need to understand the needs of their children, the family’s ability to absorb expenses, inflation, investment returns and taxation. As a result, families often end up either over- or under-saving for college. Many of them experience financial stress or find themselves decades later with hundreds of thousands of dollars in unused 529 funds, facing a dilemma about whether to pay penalties or keep the money locked up.

In this blog post we’ll discuss how you can estimate child related expenses, set up a college fund, decide how to use tax-advantaged accounts and minimize the risk of undersaving and oversaving.

Estimating Living Expenses

In the Bay Area, adding children to a household often triggers “lifestyle jumps,” such as needing a larger home or a specific school district, which can cause costs to spike exponentially.

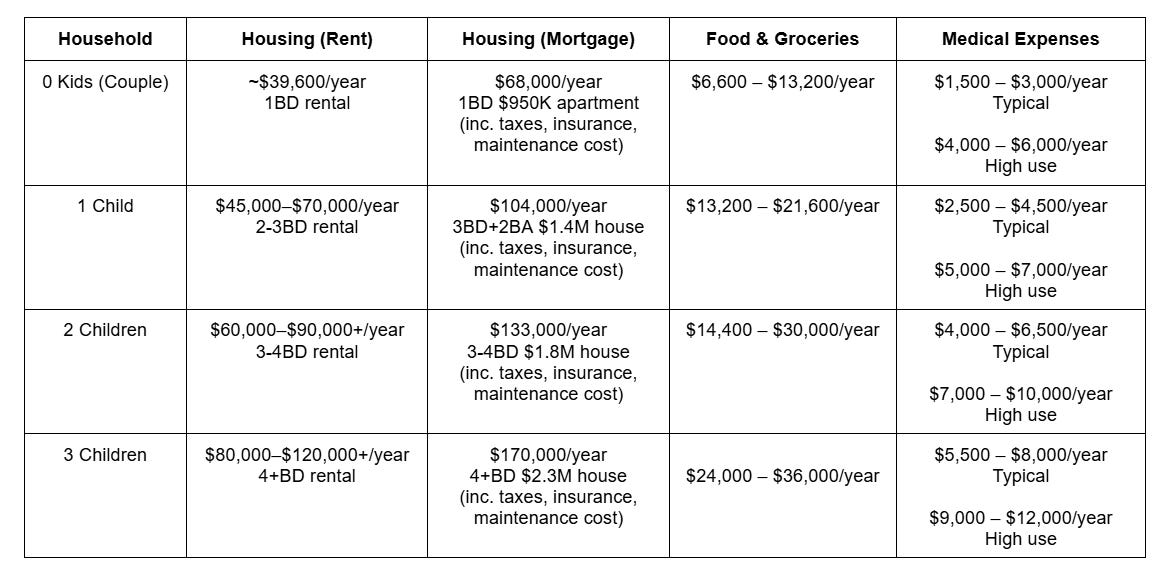

Most couples move from a 1-bedroom to a 2-bedroom when they have their first child, and it typically adds $1K–$1.5K/month in rent. If the family decides to buy a house, their annual housing expenses go up from $39.6K/year to $104K/year which includes mortgage, property taxes, maintenance cost and insurance. Food & Groceries grow 30% and medical expenses (insurance premiums and out of pocket expenses) often double.

The second child increases most family expenses. Housing increases by $15K-20K/year if they rent, and if the family decides to become owners and buy their own place, the increase in housing costs might be around $60K–85K/year. Food & groceries increase 10-20% and their medical expenses increase around 30%.

Having 3 kids is often the “tipping point” where a standard 3-bedroom home or a mid-sized SUV is no longer sufficient. Upgrading to a 4-bedroom home in a “good” district often adds another $20K-50K/year to the budget depending on whether the family is renting or owning the place.

Interestingly, the incremental cost of food and clothing per child tends to decrease slightly with more kids due to significant savings on clothes and gear for the 2nd and 3rd child. Bulk buying of groceries lowers the per-meal cost.

Development Expenses

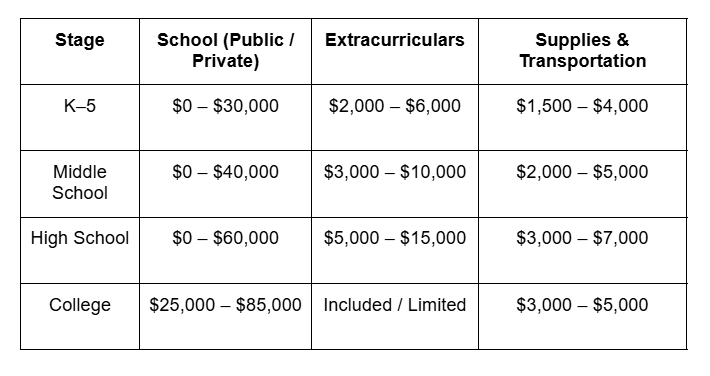

Development expenses are often the largest discretionary category in a Bay Area family budget. They include school tuition (public vs. private), extracurricular activities, supplies, and transportation, and they tend to accelerate sharply as kids get older.

Unlike housing or food, these expenses are not strictly linear — they are driven by family values, choices, and competitive pressure in a high-income environment. Two families with identical incomes can easily differ by $30K–$80K per child per year depending on these decisions.

Public education in the Bay Area can be good, especially in strong districts. However, “free” is a bit misleading. Parents still pay for after-school care, enrichment, tutoring, fundraising, and transportation. Many families move (or overpay for housing) to access better districts, indirectly converting tuition into housing costs. Private school tuition ranges widely. Modest religious or community schools may cost $12K–$20K/year. Top independent schools often range from $35K–$60K+/year.

Many families start with public schools and switch to private in middle or high school, which introduces a sudden step-change in expenses that should be modeled explicitly.

Extracurriculars are where costs quietly compound: sports teams, music lessons, robotics, tutoring. Competitive programs often require travel, equipment, and private coaching. Costs increase meaningfully in middle and high school as activities specialize. It’s common for Bay Area families to spend $3K–$25K per year per child here without realizing it.

Why College Planning is Hard

What makes planning hard for families is that inflation, investing, and taxes all interact in non-obvious ways. Education costs often grow faster than general inflation, contributions happen over many years, and investment returns are uncertain. As a result, translating future expenses into a monthly savings rate today is far from straightforward.

Tax-advantaged accounts like 529 plans can reduce taxes on growth, but they come with usage restrictions: not all education-related expenses are eligible, and not all families want to fully commit to locked-in accounts years in advance.

At the same time, families still need to account for tax provisioning: how much of future expenses will need to be funded with taxable dollars, what the marginal tax rate might be at the time, and how withdrawals interact with the rest of their financial plan. Ignoring taxes can easily lead to overconfidence in savings progress or unpleasant surprises later.

This is why education planning works best when expenses, accounts, investment assumptions, and taxes are modeled together, rather than treated as separate decisions.

Creating Financial Projection

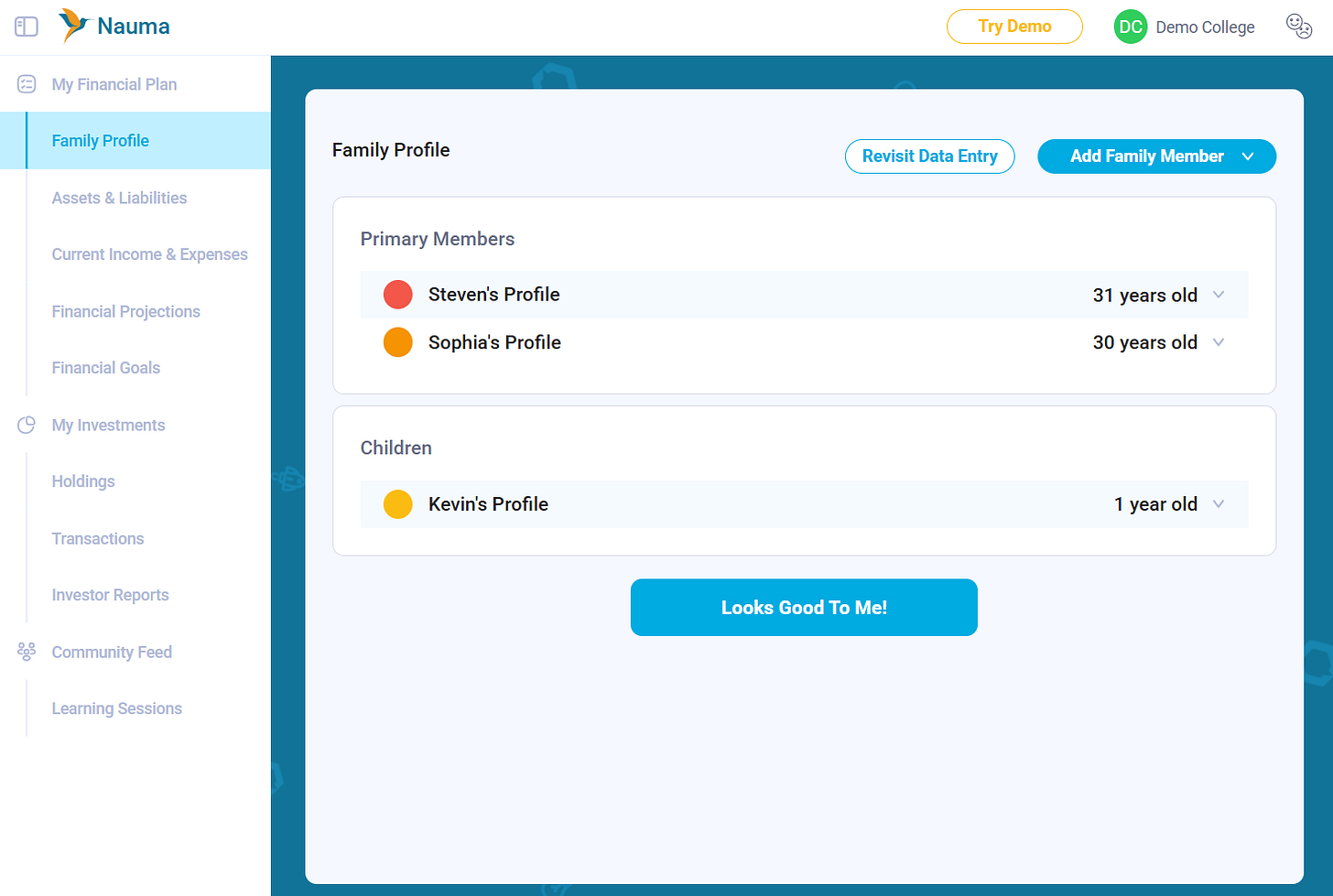

We’ll consider a family, Steven and Sophia, in their early 30s. Both work in tech and welcomed their first child, Kevin, last year. They’re expecting their second child next year. They are creating their financial plan and setting up savings accounts for their kids.

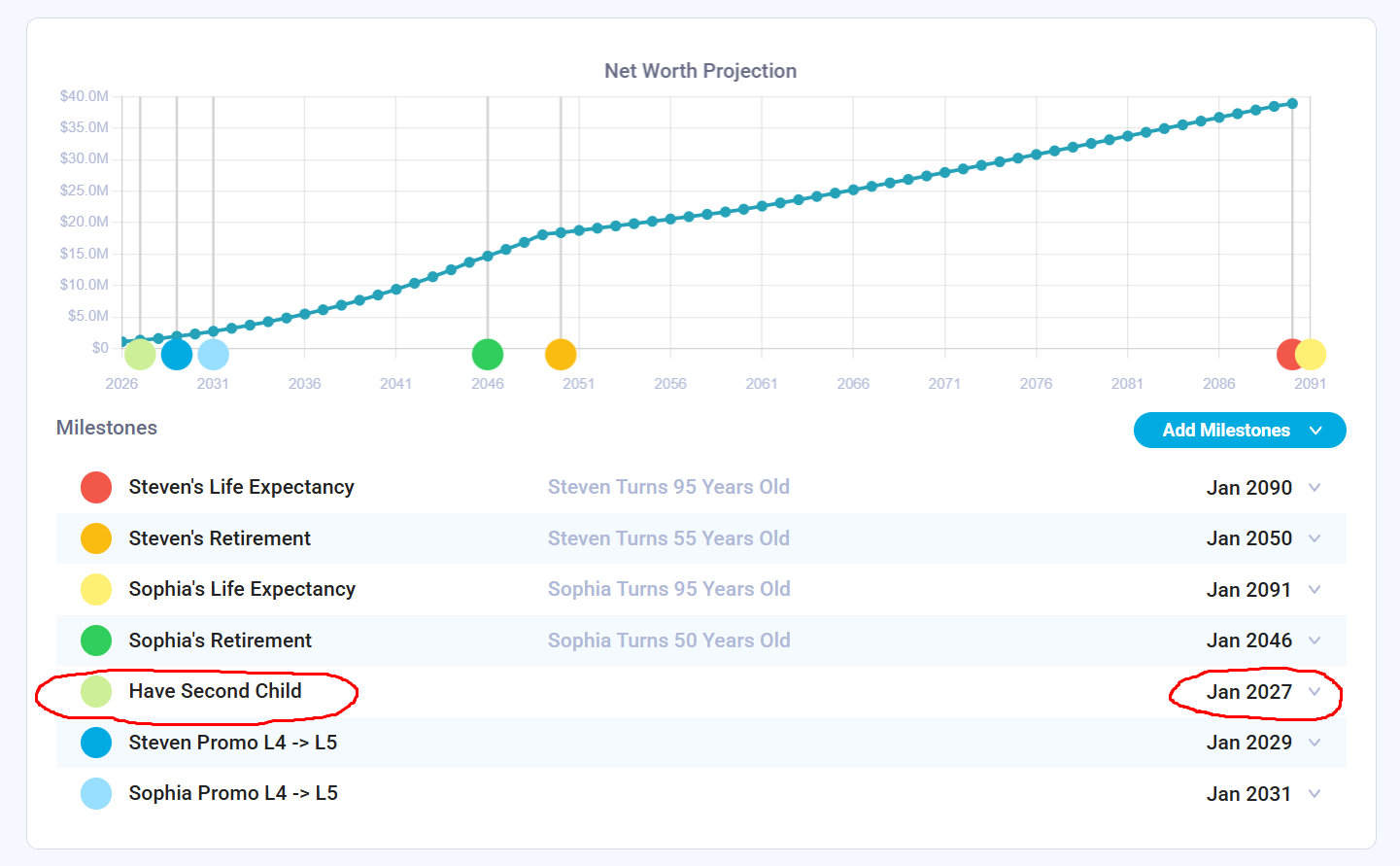

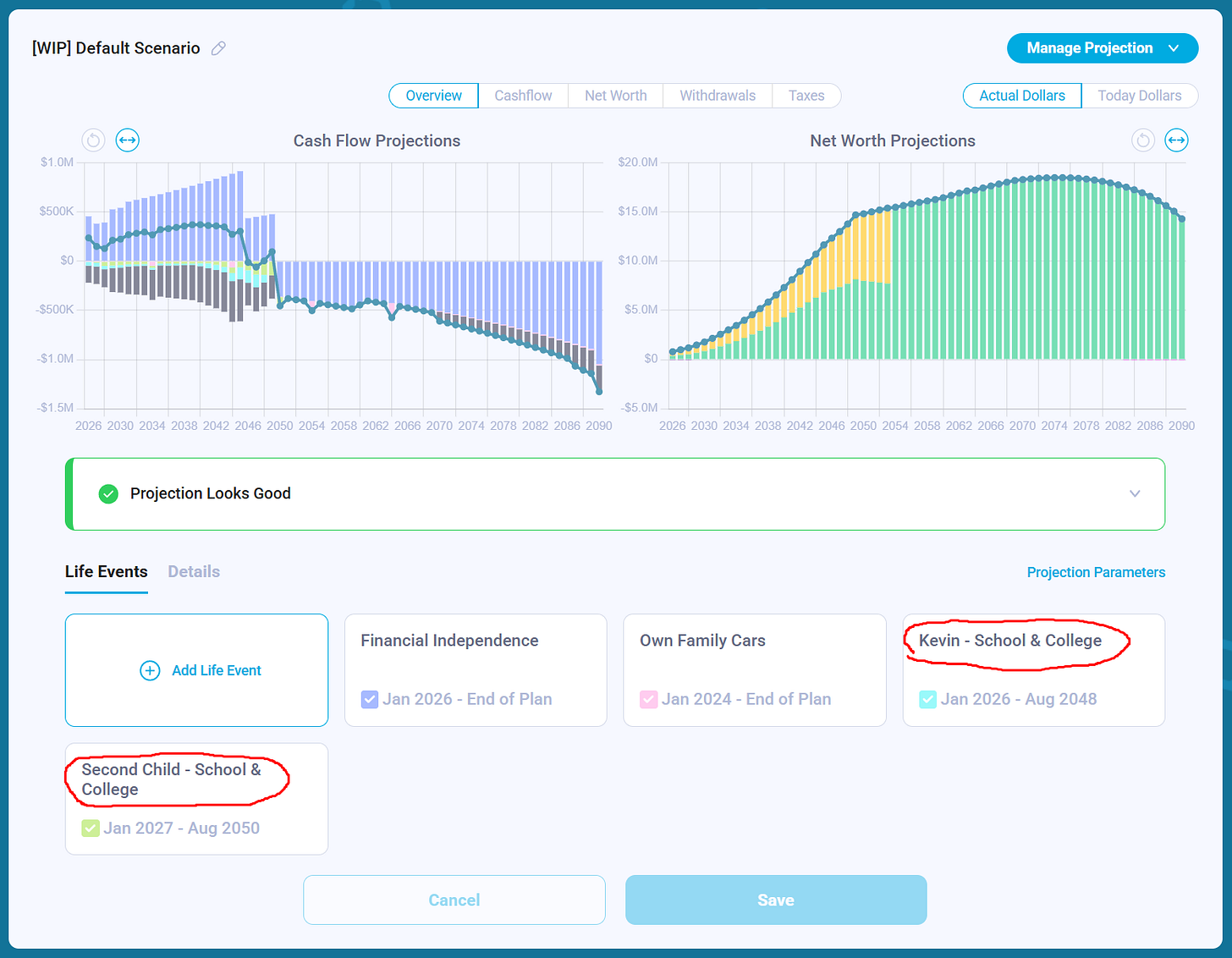

Steven and Sophia start by creating a financial projection and adding future income and expenses. They adjust their living expenses to reflect the increased costs that come with a second child and begin to see how this affects their net annual cash flow, savings rate, and net worth.

To make their financial projection adjustable and perform what-if analysis later they use Milestones. They create milestones for the most important events and then use them to set start and end dates for income & expenses in the projection. Adjusting the milestone date then automatically updates all associated income and expenses.

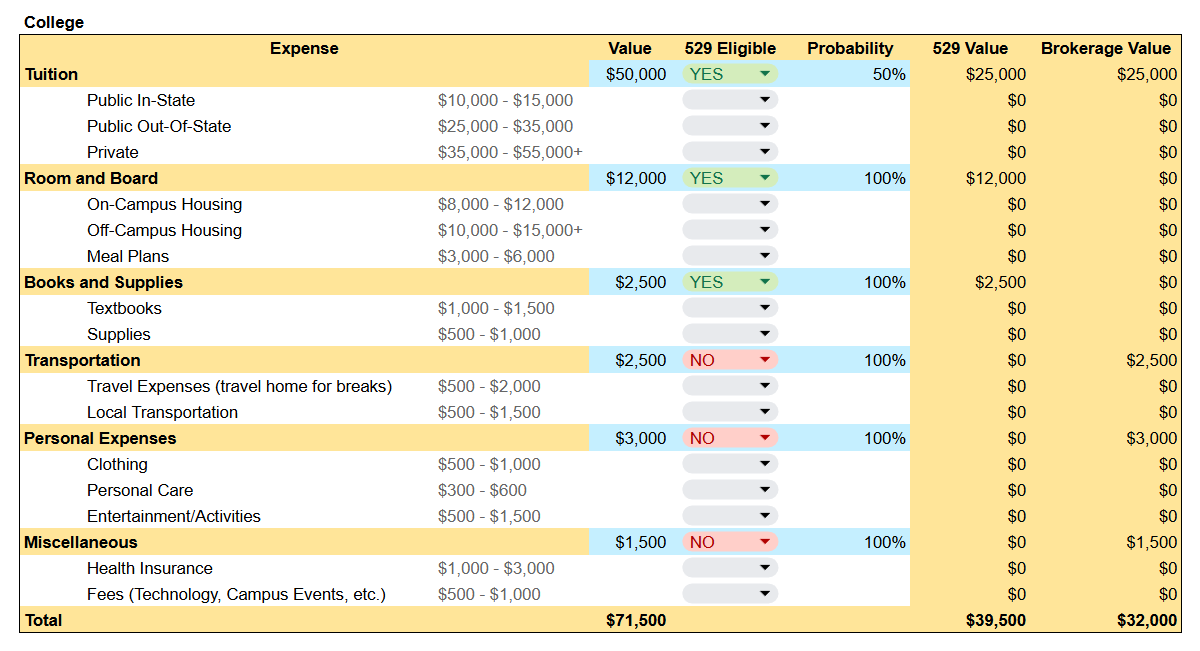

With the first version of their financial projection in place, the family can start discussing educational expenses for their kids and decide what fits their family best. To do this, they use a simple Google spreadsheet to estimate costs and assign probabilities to whether those expenses will occur. This helps them decide how to allocate savings between flexible taxable accounts and more restrictive 529 plans.

If the family is confident that a specific 529-eligible expense will occur, they can use a 529 plan for that purpose. Otherwise, they may prefer regular brokerage accounts, which allow assets to be reallocated toward other financial goals in the future.

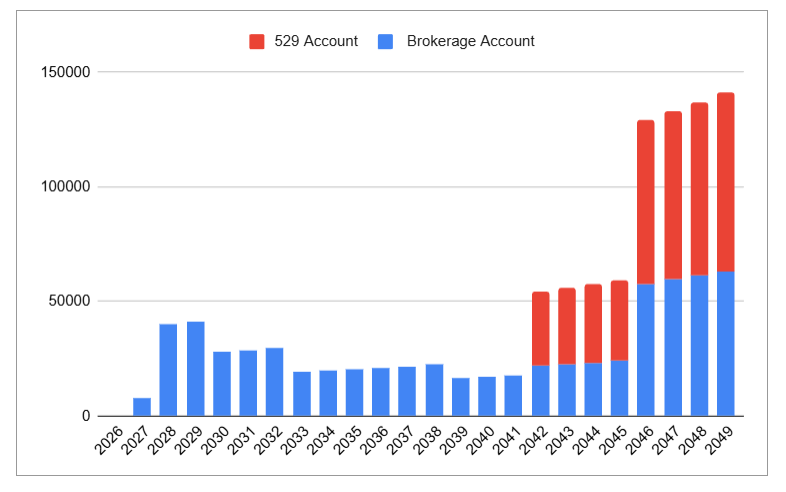

This is also a great time for partners to have open conversations and align on values and priorities. Using their draft financial projection, Steven and Sophia evaluate whether they can realistically afford these expenses and decide whether private elementary, middle, or high school makes sense for their family. They also discuss the extracurricular activities they envision for their kids. By the end of this process, they can see how expenses are expected to change over time based on their current choices for one child.

Finally, they add the agreed-upon expenses to their financial projection and observe the impact on their net worth. You can see how net annual cash flow (the blue line on the left chart) varies over time. Typically, the higher a family’s income and net worth, the more year-to-year variability they experience.

Setting School & College Fund

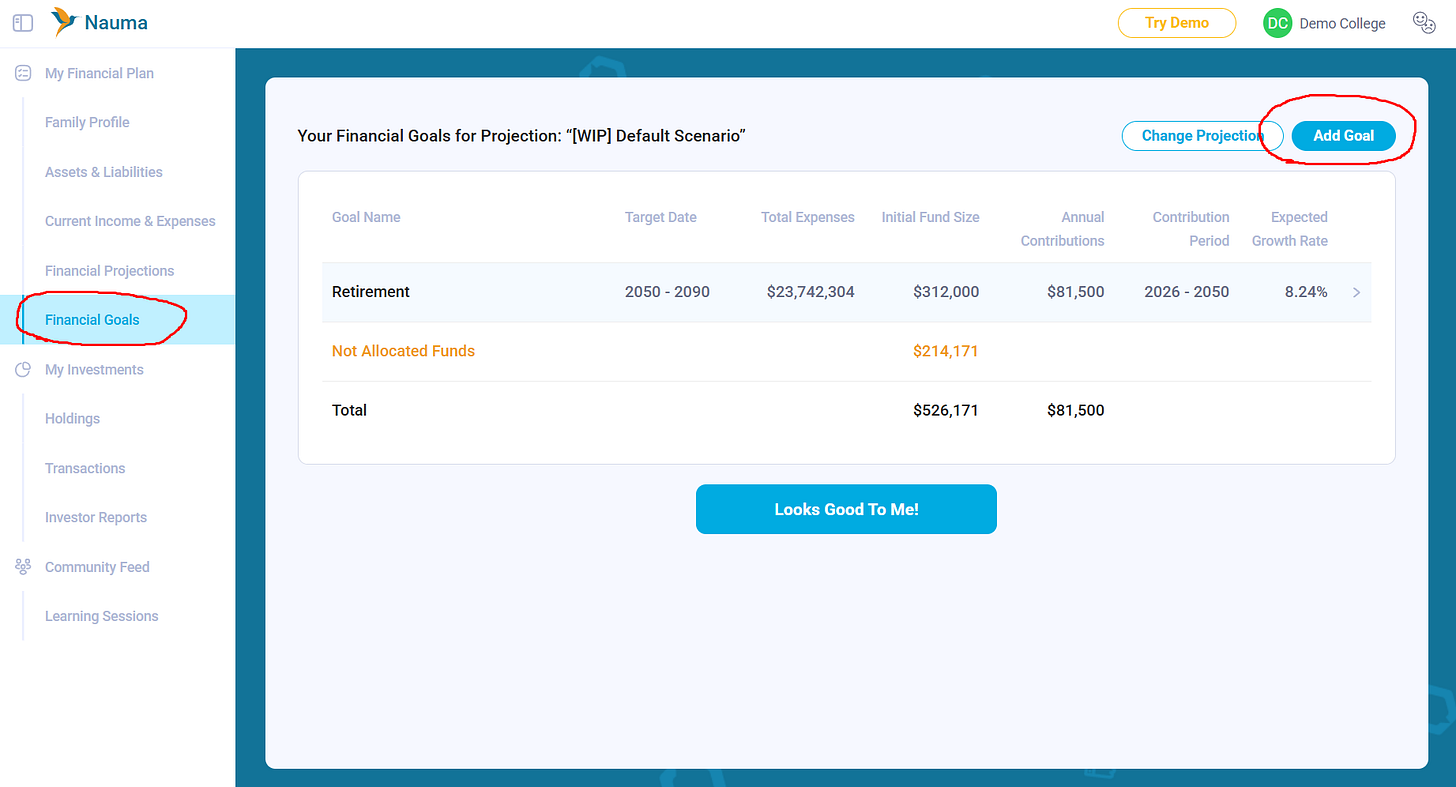

The financial projection is the first step—it shows how future expenses appear on the timeline and how they impact net worth. However, Steven and Sophia still need to determine how much to contribute to their 529 plans and taxable accounts to actually fund those expenses when the time comes. To do this, they move to Financial Goals and create a new goal.

Their objective is to choose an initial fund size, ongoing contributions, and an investment portfolio that will cover all expected education expenses, adjusted for inflation and taxes, with a desired probability of success. That probability is determined using Monte Carlo simulations.

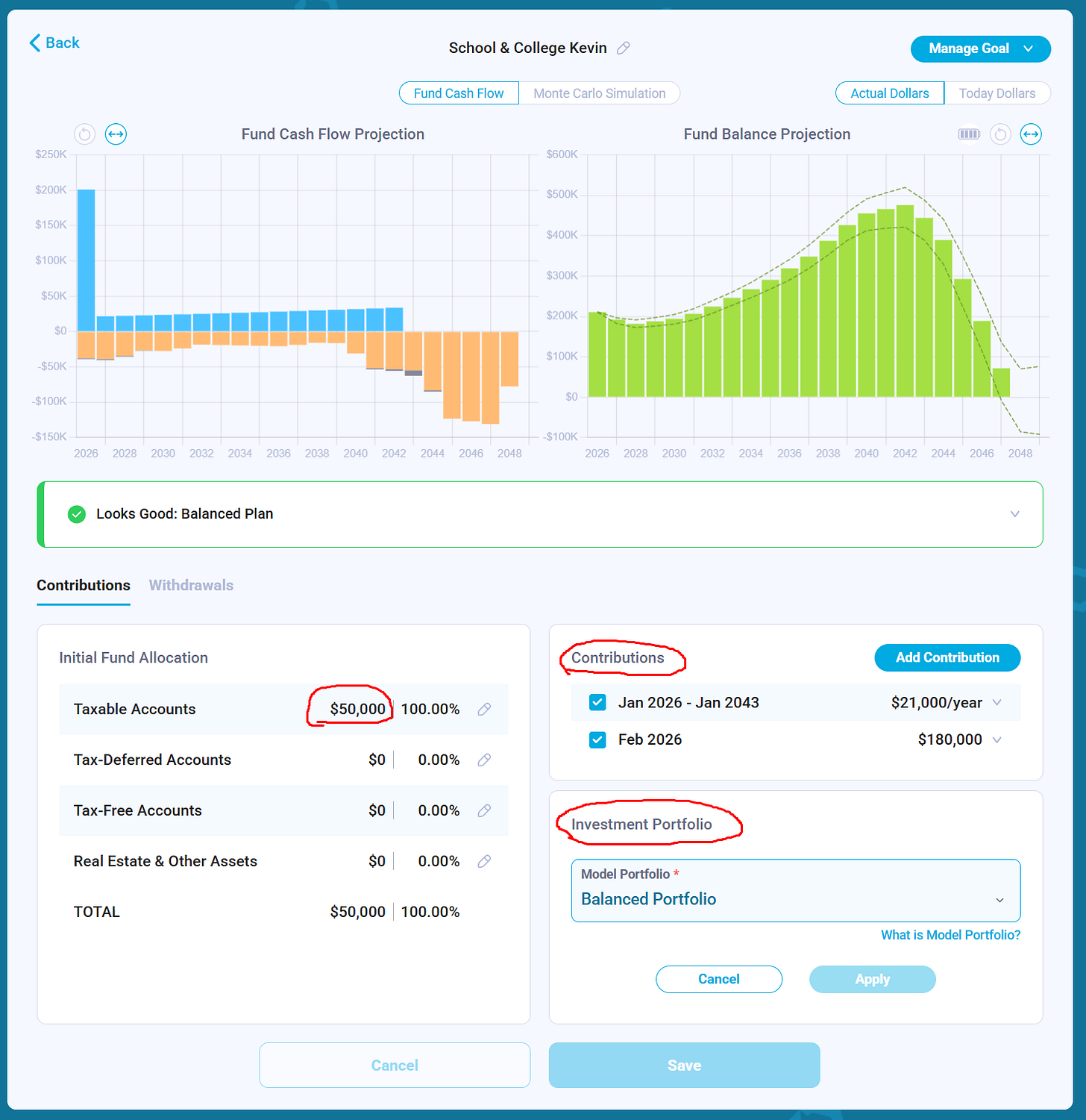

In the first scenario, they allocate $50K from existing savings and superfund their 529 plans. Together, they contribute $180K upfront ($19K × 5 years × 2 partners), then add $21K per year between 2026 and 2043. They target an 80% success probability, meaning they evaluate the 20th percentile Monte Carlo outcome when the college fund reaches zero. Other families may prefer a more conservative approach, aiming for a 90% or 95% success rate, which would require higher contributions.

In this scenario, taxes (shown as grey bars in the cash flow projection) are minimal because the family uses a tax-advantaged 529 plan and begins using contributions relatively soon after they are made. Total planned contributions add up to:

$50K + $180K + ($21K × 17 years) = $587K

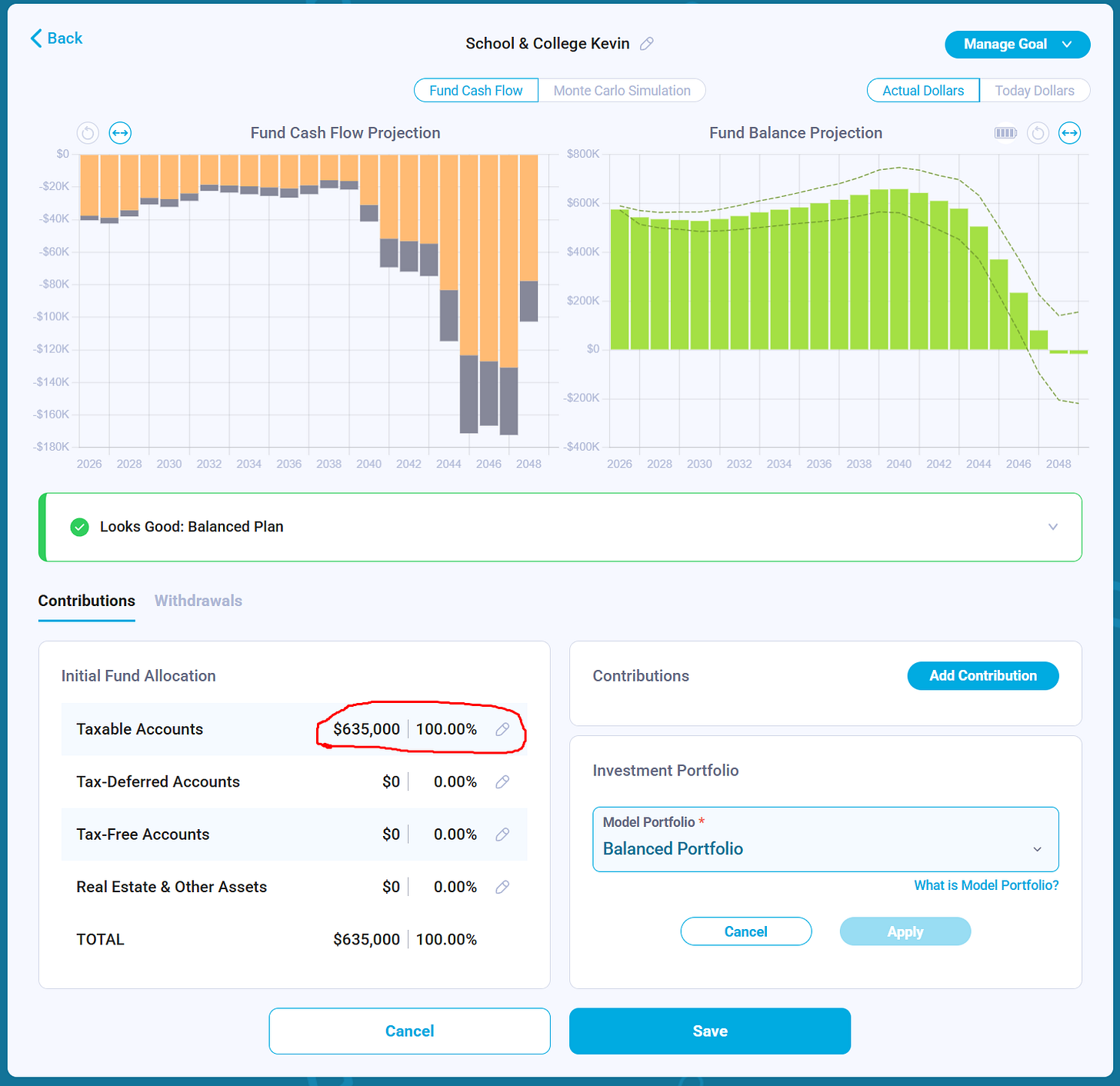

If the family already has investable assets but chooses not to use a tax-advantaged account, they would need to allocate approximately $635K to cover the same expected expenses. The higher total reflects the drag from taxes, which increases the amount that must be saved to achieve the same outcome.

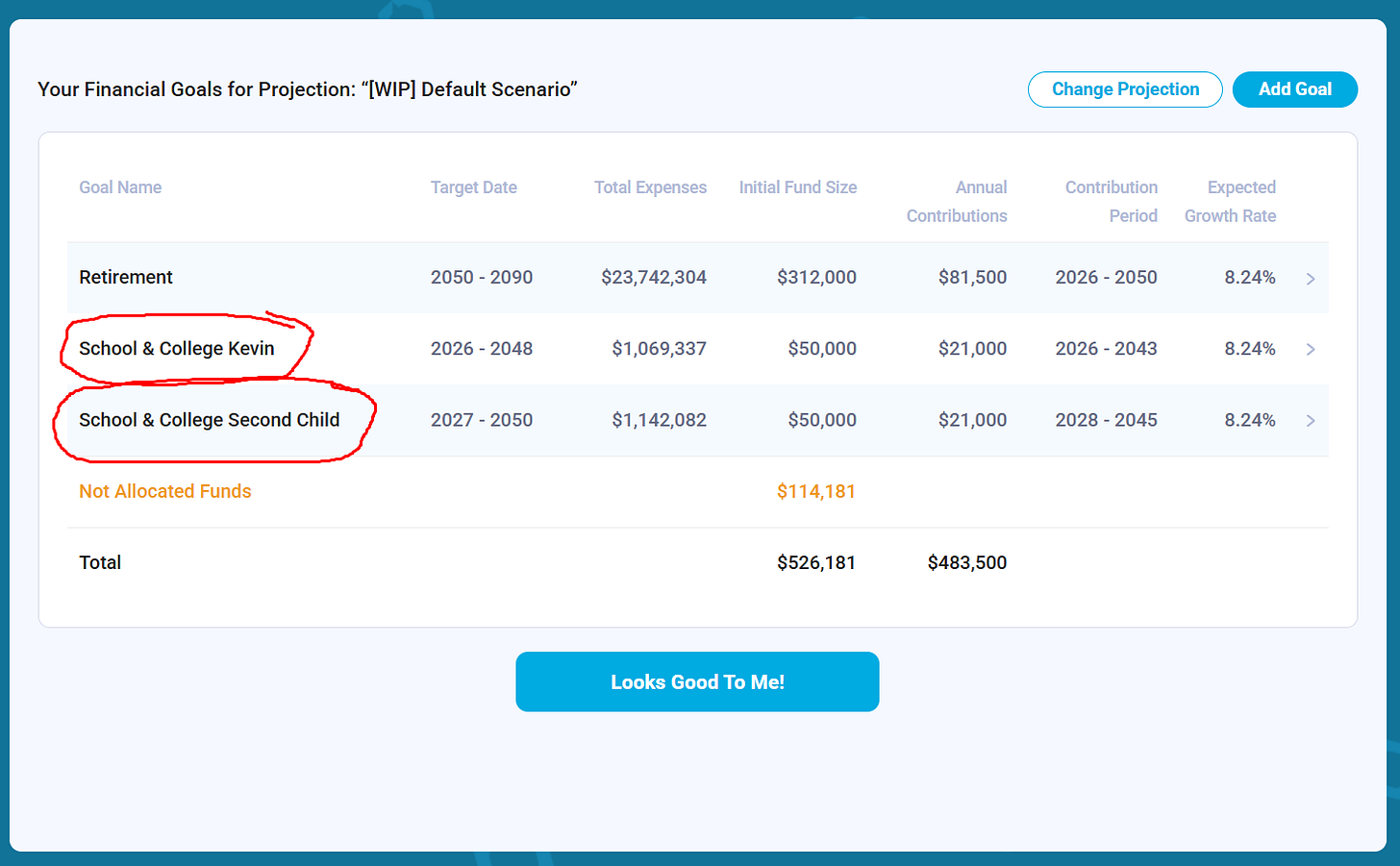

Once this process is complete, Steven and Sophia can repeat it for their second child and incorporate both education goals into their overall financial plan:

Conclusion

Raising kids in the San Francisco Bay Area is as much a financial journey as it is an emotional one. Housing, childcare, education, and enrichment expenses don’t just grow over time, they arrive in waves, often coinciding with major life decisions that compete with other goals like retirement, career flexibility, or financial independence.

The key takeaway is that education planning is not a single decision. It’s an ongoing process that requires:

Estimating expenses realistically across different life stages

Acknowledging uncertainty in inflation, markets, and future choices

Balancing tax efficiency with flexibility

Aligning financial decisions with family values, not just averages or social pressure

Families that run into trouble are rarely careless, they’re usually planning in silos. They estimate college costs without modeling taxes, commit too aggressively to 529 plans without flexibility, or delay planning until the window to adjust contributions meaningfully has already passed.

A better approach is to treat education funding as part of the overall financial system: expenses, accounts, investments, and probabilities modeled together. This allows families to make informed trade-offs, course-correct early, and avoid both the stress of undersaving and the regret of overcommitting capital.